Operation

Kosovo

photos

by Keith Nordstrom

HATE

STOPS AT HOSPITAL

BY CRAIG BORGES / SUN CHRONICLE STAFF

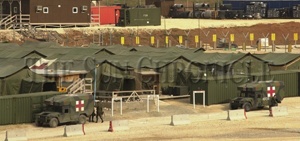

CAMP

BONDSTEEL, Kosovo - The hate and mistrust between ethnic

Albanians and Serbians astounds many here, even those

soldiers who have made the conflict between Kosovo and

it's dominate neighbor, Serbia, their focal point of

study for the past six months.

CAMP

BONDSTEEL, Kosovo - The hate and mistrust between ethnic

Albanians and Serbians astounds many here, even those

soldiers who have made the conflict between Kosovo and

it's dominate neighbor, Serbia, their focal point of

study for the past six months.

But tucked away in a jumble of tents and makeshift buildings

here at Camp Bondsteel, ethnic barriers fall and hatred,

like a heavy and tattered overcoat that has long slipped

out of fashion, is checked at the door, hopefully for

good.

This is Task Force Medical Falcon, a field hospital

at Camp Bondsteel that has been run by the U.S. Army

Reserve's 399th Combat Support Hospital out of Taunton,

since March.

Here, all are treated equally - ethnic Albanians and

Serbs alike. Albanian is spoken here, as is Serbo-Croatian.

Here there is no time or room for things like Balkan

politics, Balkan revenge or Balkan history.

Danica Nikolic, a Serb from the Kosovo town of Riniluk,

knows this first hand as does Adem Zeka, an ethnic Albanian

from the village of Begunc, near the municipality of

Vitina.

Misfortune has brought both people here, Nikolic, for

her 11-year-old daughter Sanja, who suffered an appendicitis

attack late Friday night, and Zeka, for his 11-year-old

nephew Pajtim, who underwent an operation to correct

a colon defect he has suffered with since birth.

"There is no difference here," Mrs. Nikolic

says in Serbo-Croatian through a translator, her hands

gesturing to Zeka and his nephew. "That boy, my

daughter, they are both innocent of the horrible things

that were done. Hopefully we'll get together and forget

all the bad things. Children aren't guilty."

The physicians responsible for making these two children

right again included Maj. J.C. Cortiella, who as a civilian

works at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center

in Worcester, Maj. .Tim Counihan, also of the UMass

Medical Center, and Maj. Thomas Cataldo, a Worcester

native who now works in New Jersey. All are members

of the 399th.

"We are pleased, very lucky to have this happen,"

Zeka, Pajtim's uncle, says in Albanian through the translator.

"The boy lived on only juices for 10 years. He

could not defecate because it was so painful. He is

fine now. The doctors here made this possible."

This was the second operation for Pajtim. Kosovar doctors

in Pristina carried out the first, which consisted of

putting the boy on a colostomy bag. But even basics

are difficult to get here in the ruins that are Kosovo.

Finding the bags the boy needed, proved nearly impossible

for his family. That's when a KFOR civil affairs officer

who had met the family, made the operation at Bondsteel

possible.

Under KFOR rules, civilians can be treated at the camp

hospital only if there is a threat to life, limb or

eyesight, so civilians tend to be a small part of who

the unit here works on.

U.S. soldiers and those from other KFOR nations are

the most common patients.

---------------

It's early Sunday evening and the word is passed down

- a chopper is coming in with a shooting victim. Initial

reports indicate a Serb soldier has been shot in the

back.

The 399th members swing into action.

Drs. Cataldo, Counihan, Cortiella, along with the Boston

Celtics' doctor, Col. Arnold Scheller and Norfolk, doctor,

Col. Gregory Quick, get ready.

EMTs, nurses and technicians prepare the emergency and

operating rooms.

Within

15 minutes the whir of a UH60 Blackhawk medical helicopter

is heard and suddenly appears overhead, it's heavy blades

causing a mini windstorm on the ground as the pilot

brings eases it onto a landing pad opposite the hospital's

front doors.

Within

15 minutes the whir of a UH60 Blackhawk medical helicopter

is heard and suddenly appears overhead, it's heavy blades

causing a mini windstorm on the ground as the pilot

brings eases it onto a landing pad opposite the hospital's

front doors.

Three EMTs and a translator don headphones and run in,

crouching to escape the powerful gusts caused by the

chopper's blades. They pull a bright orange stretcher

carrying a large blondish man from the 'copter's back

bay and rush back under the spinning blades, off the

pad and in through the ER's swinging doors.

Inside, doctors, nurses and EMTs surround the man, shouting

orders and working frantically to stabilize him. The

front of his t-shirt is blotted with blood.

Moments later X-ray technician, Specialist Faith Patterson

of Dorchester, rushes into the ER. Doctors order a chest

x-ray on the spot. She carries out the order with a

portable x-ray machine and then the man is rolled across

the hall to be operated on.

------------

Hours later, Army investigators report the man wasn't

a soldier, but a Serb civilian. He had been shot twice

in the upper body while sitting in a restaurant called

Café 99 in the city of Vitina, east of Camp Bondsteel.

The man, investigators said, jumped on his bike and

peddled a short distance to a Serb church being guarded

by soldiers in the U.S. Army's 1st Battalion, 325th

Airborne Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division.

They got him to the help he needed. Investigators suspect

an ethnic Albanian did the shooting.

But these are details few care at the 399th care about.

A shooting victim is a shooting victim. They announce

his condition, critical but stable.

-----------

It's

Saturday night and a Spanish Army ambulance speeds into

Bondsteel. Inside, three Spanish soldiers sit dazed,

victims of an SUV rollover somewhere in the countryside.

It's

Saturday night and a Spanish Army ambulance speeds into

Bondsteel. Inside, three Spanish soldiers sit dazed,

victims of an SUV rollover somewhere in the countryside.

Spanish Army nurses Ana Castro Marquez and Maria Garcia

Vergara, with the help of two burly ambulance drivers,

rush the soldiers in to a waiting Col. Quick.

Quick goes to work, evaluating each man for broken bones

or concussion. Later, he reports they suffer only bumps

and bruises.

Col. Quick, a former ER doctor at Norwood Hospital,

is quiet and reserved. He welcomes the opportunity to

discuss the work the 399th is doing. He says he prefers

it, in fact, over talk about the number of soldiers

and rebels the 399th has had to patch up, or see die,

since arriving.

Anyone suffering life-threatening injuries in the American

Sector usually ends up at Bondsteel.

So far the 399th has seen it's share of bloodshed, ranging

from British soldiers killed and wounded in a helicopter

crash as well as a landmine explosion, to ethnic Albanian

rebels shot during confrontations with both U.S. soldiers

and troops from other armies.

But the how and why behind the injuries don't interest

him. It's ER work and the team here is excellent at

it, he says.

"It's fun, exciting," he says. "There's

plenty to do, but it's not like an ER in the United

States. There's not that steady stream of people coming

in. It comes in spurts. We can be flat out and jammed

in here, then it will be quiet for hours on end."

Quick's wife Kitty, a former Foxboro, resident, works

as a nurse at Fuller Hospital in South Attleboro. The

Norfolk couple has three children, 21-year-old Katie,

17-year-old Pattie and 11-year-old James.

Being away from his family is difficult, he says, but

e-mail has made the separation so much easier.

"Technology has really changed things like this

in so many ways," he says. "Digital photos,

emails, phone lines. It's a big difference from years

ago."

Quick's family has practice, too. Quick much of last

year much further away from them than Kosovo, serving

as a doctor for Raytheon scientist working in Antarctica.

He says his family doesn't necessarily his overseas

adventures, but knows it's his job, his passion.

Quick says the thing he finds most interesting about

his stint here is being able to work with multinational

physicians.

"It's so international here. It's very appealing,"

he says. "You've got Greek, Australians, Russians,

Poles, so many different groups that make it so interesting."

---------

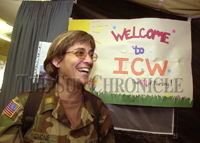

Getting

a better appreciation for different cultures is something

Maj. Gloria Vignone enjoys about her stint here in Kosovo.

Getting

a better appreciation for different cultures is something

Maj. Gloria Vignone enjoys about her stint here in Kosovo.

Vignone, who is charge of the wound care center at Sturdy

Memorial Hospital in Attleboro, leads the Intermediate

Care Ward here at Bondsteel. Her job, she says, is to

mentor enlisted soldiers.

The Johnston, R.I., resident has been with the 399th

for 12 years. She says the work here can be excessive

- 12-hour days, six to seven days a week, but it has

given her a new appreciation of all that she has in

the United States.

"It's sad out here, really," she says. "The

people have nothing and we have so much."

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Copyright 2001

The Sun Chronicle